It was a beautiful afternoon in Southern Kenya; the Maasai tribe was thriving, and I was helping my mother cook dinner for our family. I was eight years old, just the perfect age to learn mamangu’s (my mother’s) recipes, and tend to the children while the adults were busy. I tried to help take care of the kin all around the village, so that the mothers of the Maasai could talk amongst themselves and enjoy their time together without being bothered. I considered myself a great help around the village, and the adults would often thank me with small gifts like an extra slice of bread or extra time in the bath. I enjoyed helping out and feeling as though I was an important part of the Maasai tribe. So when the day came that my mother asked me to fetch water from the brook all by myself to help her cook a meal, I felt proud and honored, and I graciously accepted.

From the tribe’s grounds, the brook is quite a ways away. To get there, I have to cross through all of the huts of the Maasai village, all the way to the other side. Then I must follow the small path, past the big beautiful acacia tree, until I see a fork in the paths; I follow the farthest path on the right to its very end where I must walk through tall grass and weeds until I can finally feel the muddy soil beneath my feet. That’s when I know I’m almost there. All the while, I have a giant bucket over my head that I have to carry the whole way. It is about seven miles in all, and takes me close to three hours to get there. It takes me longer to get back, though, because I am already tired, and the bucket is harder to carry during the second trip because it is mostly full.

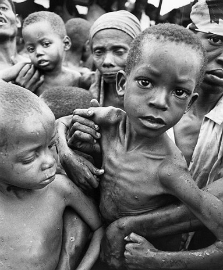

It is not uncommon to see young boys and girls helping their mothers gather water at the stream, so that the mother does not have to make several trips. We also share a stream with the cattle of Southern Kenya, so it is usual to see more than one animal at the brook while you are there. It is also important to understand that the brook is the central part of Kenyan life; every member of the nearby tribes comes here to retrieve water for drinking, cooking, bathing, and washing. So, more often than not, beggars and people without family come to the brook, hoping that someone, anyone, will give them something to eat or wear or even a place to stay. These people are what make the brook a very dangerous place for children to come alone.

Although I was a bit nervous to be travelling on my own for the first time, I gained comfort from the thought that my mother and the other women of the Maasai were awaiting my return. If I did not come back in a few hours, I know that the children would look for me. Mamangu would look for me. Everyone would look for me. Because the Maasai tribe is like a family; we look out for one another, protect each other. I was sure I would be safe.

At the stream, I had a difficult time collecting water. Every time I would lean down to gather water, more water would fall out of the bucket than into it. Frustrated, I wondered to myself how my mother collected so much water for so many years, all by herself. I thought about how I had to perfect the art of gathering water, so that I could cook food for my children. And maybe someday I would ask my daughter to fetch water for me.

Because I had been daydreaming, I didn’t notice the man who was trying to get my attention. When I finally snapped back into reality, I jumped at his voice.

He was a friendly middle-aged man, who could not have been from the Maasai tribe because I didn’t recognize him. He had the darkest complexion I had ever seen, and his teeth were yellow and his clothes were dirty. Everyone’s teeth were yellow. Everyone’s clothes were dirty.

He smiled a big smile at me when I turned around. Laughing, he asked me if I needed any help fetching water. He said he could tell it was my first time, and that he could help me if I wanted.

Although I didn’t know the man, I was pleased by his offer. He was right, I had never done this before… at least on my own. And as he helped me fill up the bucket with water and take most of the sand and dirt out, he asked me my name and about my day.

“Naomi,” I said, smiling. “My name is Naomi.”

I told him that I was a member of the Maasai tribe and that my mother had asked me to fetch water for dinner tonight. He told me that I had better hurry up and get back before it got dark.

“Those woods are a dangerous place for a small girl like you,” he told me.

When we were finished filtering the water, I thanked him, put the bucket on top of my head, and began walking. I almost dropped the entire bucket of water when I tripped over a dense pile of wet sand. But I caught myself.

I heard him laughing from a distance, so I turned around and smiled nervously. I was embarrassed that he had seen me trip. Before I could make it to the section of tall grass and weeds, he asked me if I needed some company on the walk back.

“I’m headin’ that way, anyhow,” he told me with a smile.

As we walked, the sun began to set. It was getting chilly but I was all right. I was glad I had someone to talk to on the walk; the woods were so dark and cold, I would’ve been afraid to walk by myself. He offered to carry the bucket so I wouldn’t have to struggle with it. He told me I would get home faster that way, and he wanted to make sure I made it home safely.

******************************************************

I wiped the tears from my cheeks as I emerged from the darkness of the woods. My knees were bleeding. My body was aching. Time was going by so slowly. The bucket I had been carrying felt heavier than it ever had before; the water looked so clean, but I felt so dirty.

When I returned to the village, my mother was waiting; she had asked me to be careful, and I told her I was. She asked if I made it there and back okay. I said yes.

I no longer felt like myself. I no longer felt like an eight-year-old girl. I felt like a grown woman, in the worst sort of way.

There are no answers. There’s no reason why. I’m just another girl in Kenya. Just another story, another crime, another form of suffering left to be ignored.

Her smell. Her touch. The warmth of her body. I remember it all. I remember the last time I saw her; the last time I was able to smell her, touch her, feel her. We never did have it easy; I only ate every couple of days, and I had been given a blue cup that I carried around with me begging everyone I saw for water. She gave me everything she could, everything she had. Even when we were hungry and cold and thirsty, she’d still be humming me to sleep, telling me everything was going to be okay. I don’t think I ever saw her without a smile on her face. Until the day they came.

Her smell. Her touch. The warmth of her body. I remember it all. I remember the last time I saw her; the last time I was able to smell her, touch her, feel her. We never did have it easy; I only ate every couple of days, and I had been given a blue cup that I carried around with me begging everyone I saw for water. She gave me everything she could, everything she had. Even when we were hungry and cold and thirsty, she’d still be humming me to sleep, telling me everything was going to be okay. I don’t think I ever saw her without a smile on her face. Until the day they came.

Africa dear Africa

Africa dear Africa

This photograph, taken by Jodi Cobb from National Geographic Magazine, shows a Mursi Tribeswoman. "Among the Mursi tribeswomen of Ethiopia's Omo Valley, lip plates are a source of pride and a sign of strength. When a girl is 15 or 16, her lower lip is cut and held open by a wooden plug. Over the next several months, progressively larger plugs are inserted to stretch the lip. Not all girls continue until they can wear plates of the size shown here."

This photograph, taken by Jodi Cobb from National Geographic Magazine, shows a Mursi Tribeswoman. "Among the Mursi tribeswomen of Ethiopia's Omo Valley, lip plates are a source of pride and a sign of strength. When a girl is 15 or 16, her lower lip is cut and held open by a wooden plug. Over the next several months, progressively larger plugs are inserted to stretch the lip. Not all girls continue until they can wear plates of the size shown here." This is a photograph taken by Remi Benali/Getty Images. It shows a Hamar Tribeswoman from Omo Valley in Ethiopia. "All Omo Valley tribes wear traditional attire and adornments, but the Hamar, like this woman, are by far the most elaborately turned out, often sporting multiple beaded necklaces, armfuls of metal bracelets, and elaborate, sculptured hairstyles."

This is a photograph taken by Remi Benali/Getty Images. It shows a Hamar Tribeswoman from Omo Valley in Ethiopia. "All Omo Valley tribes wear traditional attire and adornments, but the Hamar, like this woman, are by far the most elaborately turned out, often sporting multiple beaded necklaces, armfuls of metal bracelets, and elaborate, sculptured hairstyles."